These short texts are narrating the story of some of the women who were killed by the Islamic Republic.

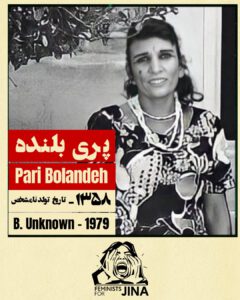

Pari Bolandeh (Pari the Tall, the Tall fairy) (b. unknown – 1979)

Sakineh Ghasemi (known as Pari Bolandeh or Pari the Tall) was a sex worker in Tehran’s Shahr-e-Now. She and a few other Shahr-e-Now women were arrested following an arson that destroyed their neighborhood in the 1979 revolution. Her name is listed amongst the 438 persons who were put to death between 1979 and 1980 in a report by Amnesty International. According to Keyhan Newspaper, Pari Bolandeh and two other sex workers, Saheb Afshari (Suraya the Turk) and Zahra Afiha (Ashraf the-four-eyed), were sentenced to death by the Islamic Revolutionary Courts for “corruption on earth.” They were executed – reportedly by a fire squad – in 1980.

Shahr-e-No (literally meaning The New City), a neighborhood in the outskirts of Tehran, was remodelled during the Pahlavi era (Reza Shah’s time), in an attempt to control sex work and sex workers. Kaveh Golestan, curated an extensive collection of photos which depict the dire misery and poverty of life in Shahr-e-No. Many women and children living in Shahr-e-No had no identity card. It was on January 30th 1979 that a large group of Islamists broke into homes in the neighborhood, destroyed them, and then set them on fire. The invasion and devastation of Shahr-e-Now and its inhabitants was one the most brutal and deadly events of 1979. The remaining pictures show that the invaders paraded a woman’s burned body through the streets for the public to see.

Of Pari herself, we know close to nothing. The details of her trial were also never published. We do know, though, that she spent some time in prison in the 1970s, prior to the revolution. Atefeh Jafari, a Fadaiean-e-Khalgh guerrilla who was also imprisoned at this time, wrote the following in her prison notes:

“We called those imprisoned for crimes, “ordinaries” and ordinary women called us, “politicals.” Pari the Tall was a beautiful, courageous and trustworthy woman. The ordinaries were once quarreling with the prison’s doctor over the distribution of pain killers. In the midst of all those cursing and foul language, Pari suddenly shouted out: “Well, maybe like these political prisoners we should also roll the picture of the Shah and shove it up our ass so that we are taken care of like them?”.

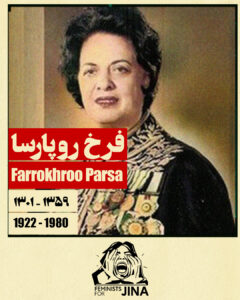

Farrokhroo Parsa (1922-1980)

Farrokhroo Parsa was born in 1922. Her mother, Fakhr-Afagh, was a women’s rights activist and editor in chief of Women’s World. Farrokhroo earned her medical degree in 1950 from University of Tehran. In 1960, she was appointed secretariat of National University of Iran amid heavy criticism of her gender. In 1964, she was elected to the National Consultative Assembly, and in 1968, she became the deputy minister of education, the first woman to hold such a position. During her tenure, Farrokhroo, established multiple organizations, assemblies, and councils for school girls and university students. Towards the end of her tenure, she tried her best to prevent the arrest of teachers protesting the Shah’s rule and in 1974 she resigned from office.

In 1980, Farrokhroo was arrested and tried by the Islamic Revolutionary Court, led by Sadegh Khalkhali, for “plundering the national treasury” and “causing corruption and spreading prostitution.” She was sentenced to death by hanging. In a botched execution, Farrokhroo was ultimately shot to death after the rope used to hang her broke. It is said that morgue workers refused to wash her body because she was called, “Corrupt of the Earth.” Instead, women family members washed her body. Farrokhroo denied all allegations until the very end.

She wrote in her will, “I do not have a will because I do not own much and whatever I had has been confiscated … My conscience is clear that I have not committed the wrongdoings I have been accused of. Give my prayer mat that holds my rosary, watch and ring to my husband to give to my daughter. The court discriminates heavily against women and I hope for a better future for women in Iran. Divide the money I have in prison amongst the prisoners.”

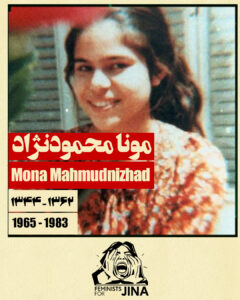

Mona Mahmoodnejad 1965 – 1983

Mona Mahmoudnejad was born to Iranian Bahai parents in Yemen in 1965. She returned to Iran with her family in 1969 when Yemen expelled all foreigners. In 1982 at the age of 16, Mona, along with her father and a number of other Bahais, was arrested and tried for teaching the Bahai faith to children. That year Hojjat-ul-Islam Qazai, head of the Islamic Revolutionary Court of Shiraz and Sharia ruler of Shiraz back then, was personally involved in the mass executions of Bahais. In several interrogation sessions, Mona was told to deny her religion in order to avoid the death sentence, but Mona refused.

In November 1983, Mona was executed along with nine other Bahai women. She was only 17 years old and the youngest among the executed. Mona’s father was executed some months before her and her mother also spent several months in prison. The judicial authorities of Shiraz did not inform her family about Mona’s execution. Her body was buried without her family’s knowledge in a mass grave, without washing and without any ceremony in the Bahai cemetery of Shiraz.

According to Taraneh, Mona’s sister, she was a skilled writer and a few months before her arrest she wrote an essay in school protesting the oppression of the Bahai community in Iran. The topic of the essay assigned by her teacher was “Islam is a tree, the fruit of which is freedom.” Mona wrote in part, “Why are my fellow believers being kidnapped from their homes in my country? Why are they taken to mosques at night in their sleepwear and flogged? Why are their homes being looted and set on fire, as we have seen recently in Shiraz? Hundreds of people leave their homes out of fear. Why? Because of the blessing of freedom that Islam has brought? Why can’t I express my opinion freely in this society?”

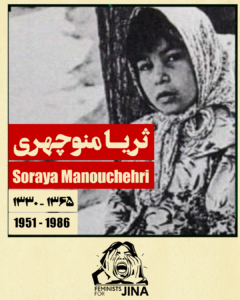

Soraya Manouchehri, 1951 – 1986

Soraya Manouchehri was born in a village called Koohpaye, in Isfahan Province in 1951. At the age of 35, she was accused of adultery and sentenced to death by stoning. Soraya was married to a prison guard who wanted to marry another woman. Unable to afford the expenses of two families, he sought a divorce. Soraya, a mother of 7 children, demanded her rights. Her husband refused to pay back her dowry and instead, with the help of the village headman and the judicial system, prepared a case against her on the fabricated charge of adultery, which ultimately led to her death by stoning.

Soraya Manouchehri’s name found its way to the public psyche through the 1994 book,”The Woman Who Was Stoned,” written by French Iranian journalist Fereydoun Sahibjam. The book documented Soraya’s life based on accounts from her aunt. In 2007, a film based on the book was internationally released titled “The Stoning of Soraya M.” The widespread circulation of the movie and the 2009 news of the stoning sentence for another Iranian woman, Sakineh Mohammadi Ashtiani, were followed by widespread international protests.

Although there has been no reliable news about the implementation of stoning in Iran in the last decade, stoning still exists as a punishment in the criminal code and has yet to be abolished. There are no other details about Soraya Manouchehri’s life, and only one photo of her is publicly available.

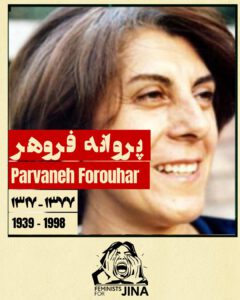

Parvaneh Eskandari (Forouhar) 1939-1998

Parvaneh Eskandari was born in 1939 in Tehran. She started political activism from a very early age and was arrested for the first time at the age of 12 for sloganeering. Arrested multiple times by the SAVAK (Intelligence and Security Organization of the Country), Parvaneh Eskandari was one of the leaders of the student movement before the 1979 revolution A supporter of Mossadegh, she was one of the main spokeswomen of the July 20th, 1961 demonstrations. Later she became a leading member of The National Front of Iran and then the second ranking member in the party. The party was based on the pan-Iranist movement and her husband, Dariush Forouhar was one of the founders of the party and later its leader. Dariush Forouhar was also the Minister of Labor of the interim government of Mehdi Bazargan.

However, in 1980 the Forouhars joined the ranks of opponents of the Islamic Republic. In the interim government, Parvaneh was the only minister’s wife who did not wear hijab. She was also one of the few political activists who objected to Khomeini’s order for annulment of family support law. According to her daughter, Parastoo Forouhar, Parvaneh Eskandari was enraged and deeply saddened by the execution of Farrokhrou Parsa, the former Minister of Education in 1980, shouting to her husband: “What do you do then?… what do you do?” Parvaneh Eskandari’s sharp criticism of the Islamic Republic was always more intense than her party’s positions.

In 1995, replying to a journalist who had asked about opposition forces and the unity front both inside Iran and outside, she said: “Could such a front succeed alone, outside the country? It is in Iran that this front should be formed, and the forces that express their solidarity abroad are indeed a mental support, and the forces that support them here will certainly follow them; however, the fundamental thing is in Iran; the origin is here; it is in Iran that we should reach such unity.”

Parvaneh Eskandari and her husband were brutally stabbed to death in 1998. Their assassination were part of the chain murders from 1988 to 1998 carried out by agents of the Ministry of Intelligence. The murderers later admitted that they killed Dariush Forouhar with 14 knife stabs, then shouting out “Yaa-Zahra” (Oh Zahra); they stabbed Parvaneh 24 times.

Alongside her political activism, Parvaneh was also a poet. The collection of her poems was published posthumously by Parastoo Forouhar. Here are some lines from her poem titled “maybe one day”:

One day

maybe

with the flight of a loving swallow,

the word Smile, will come back to my burnt land.

Hope, will knock on the door,

And white will replace all black,

On that day,

Even for the dead, I will not wear black,

Even for the most beloved of the dead.

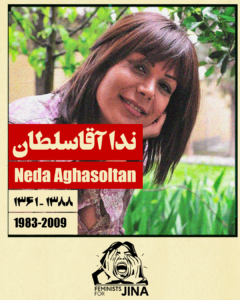

Neda Agha-Soltan (1983-2009)

Neda Agha-Soltan was born in Tehran in 1983. The second of three children, she initially studied theology at Tehran Azad University before leaving to shift her focus on photography and tourism. According to her family, she was very courageous, an avid fan of music and dance, and her favorite singer was Googoosh. Neda was killed during the protests contesting the outcome of the Iranian presidential elections in July 2009. Her death was recorded by one of the protesters. In this footage we see a group of people trying to save her life, her body soaked in blood. This image of her death became one of the most painful and emblematic representations of the protests.

Hajar Rostami, Neda’s mother, never gave up seeking justice for her daughter. In various interviews, she explains how the Islamic Republic’s agents tried to lie about the cause of her death as well as silence the family. Regarding the issue of Neda’s Diya (blood money) she said: “Shahriari, the judge, told me that I should accept the Diya. I said no, I don’t want it. Find my daughter’s murderer. The Diya is of no use to me.”

One of the witnesses of her death reported that he had seen protesters apprehending a motorcyclist as the killer. They took away his gun and also his ID card which showed he was a Basidji. The killer did not deny having shot Neda, and was heard shouting: “I didn’t want to kill her.” The protesters were afraid of being arrested themselves by the police and decided that handing him over to the police would be useless. According to the witness, they took a photo of him and his Basidj ID card and let him go.

Despite the widespread circulation of the video of her murder and statements by eye witnesses, the Islamic Republic’s authorities claimed that Neda Agha-Soltan’s killing was a fabrication made by computer software in order to destroy the image of the Islamic Republic. Thirteen years have passed and Neda’s killer has yet to be brought to justice.

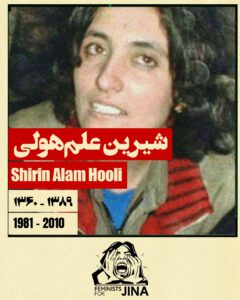

Shirin Alamholi 1981-2010

Shirin Alamholi was born in the village of Dim Qashlaq, close to Maku, in June 1981. In 2007, she was charged with detonating a bomb at the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps’ headquarters, where she was held for 25 days, before being transferred to Evin Prison. There, Shirin wrote a number of letters, describing the severe physical and mental torture she suffered at the headquarters, which left her with head injuries, internal bleeding, and vision impairment.

Denied the right to counsel for the first few months of her detention, she was thereafter granted only two visits from her lawyer. Judge Salavati sentenced her to death in 2009 for “communicating and collaborating with and being a member of the Pejak group, as well as illegal entry and exit of the border.” One of the court’s most important pieces of evidence at her trial was her confession written for her in a language that she did not know (in Shirin’s words: “Mr. Interrogator! I couldn’t even speak your language when you were interrogating me,”) and signed by Shirin after days of torture. She later retracted this confession.

On May 9, 2010, Shirin Alamholi and four other Kurdish prisoners, including Farzad Kamangar were hanged. Neither Shirin nor her family knew that the sentence would be carried out that day. After that were Shirin’s family informed that since she was a ‘warmonger,’ she would not be buried in the Muslim cemetery. There is still no information about Shirin Alamholi’s burial place after more than a decade.

According to her friends, Shirin Alamholi loved life. After learning to read and write in Farsi in prison, she penned one of her last letters; “Why am I imprisoned or sentenced to death? Is the answer because I am Kurdish? So I say: my language is Kurdish, the language I grew up with and which is a connecting bridge for me. I’m not allowed to speak, read, write or study this language, I don’t deny being Kurdish because it’s like denying myself.”

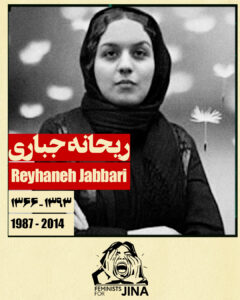

Reyhaneh Jabbari (1987 – 2014)

Reyhaneh Jabbari was born in 1987. In 2007, she studied computer science at university and worked as an interior designer. Reyhaneh met Morteza Abdolali Sarbandi, a former employee of Iran’s Ministry of Intelligence, in an ice-cream shop. When Sarbandi overhears Reyhaneh talking about her job, he introduces himself as a doctor and asks her to do the interior design for his medical office. A couple of weeks later under the pretext of the design project, Sarbandi takes Reyhaneh to an apartment. Once there, she realizes that he has lied to her and is planning to rape her. In her later letters from prison, she describes these moments : “On that Saturday afternoon of July 7th 2007, I was 19 years old and, at the moment when I got up from the chair, my whole body was paralyzed. I was cold as ice; right now I write these lines with a frozen sweating body. My legs did not follow my command, they wouldn’t run and he was so close to me. Suddenly something broke inside of me, as if someone had poured boiling water on my frozen body. I ran to the door and turned the handle. It didn’t open. He laughed with his eyes, “Where do you want to go? It is locked.” Reyhaneh manages to grab a kitchen knife, stab Sarbandi and run away. After escaping she notifies the emergency room about Sarbandi’s injuries. She then returns home for the last time ever. After her arrest, Reyhaneh was repeatedly tortured to give forced confession. Despite abundant evidence testifying to Sarbandi’s deception of her, his intention to rape her, as well as it being involuntary manslaughter, the Islamic court in 2009 sentenced her to Qisas (execution according to Shari’a law). on 25th October 2014, Reyhaneh Jabbari was executed by hanging. “I, Reyhaneh Jabbari, am 27 years old. With a rope in front of me, of which I have no fear. If I am writing this it is to recount what happened to me. Precisely and completely. I want to say all those things I shouted out in the court and they did not listen to, all that I said under the brutal torture of those four interrogators who thought they were God, all that I cried out and was unheard. Maybe there will be an ear in this world who would hear my voice and realize what happened to me”.